The Meatframe Fallacy

Vanity Engineering and the Meatframe Fallacy

In robotics, the obsession with humanoid form is often framed as innovation. In truth, it is more frequently nostalgia in a lab coat.

Designing machines to look like us is not a breakthrough. It is a mirror. And like most mirrors, it reflects vanity more than insight.

There are good reasons to build human-shaped robots. A caregiver bot should feel familiar. A classroom assistant might need to sit in a chair and gesture. In these cases, the illusion of humanity is part of the emotional toolkit. When trust, comfort, and relational ease are the job, form is function.

But outside these empathy zones, the meatframe is a constraint. Why give a restaurant kitchen robot two legs and opposable thumbs when six arms on a rail would outperform every sous chef alive? Why force a warehouse loader to pretend it has knees when wheels and wings would be better? Biologic evolution gave us bipedalism not because it was optimal, but because it was what happened to work. We are not the pinnacle of efficiency. We are the product of workaround stacked on workaround.

Robotics can do better. Should do better.

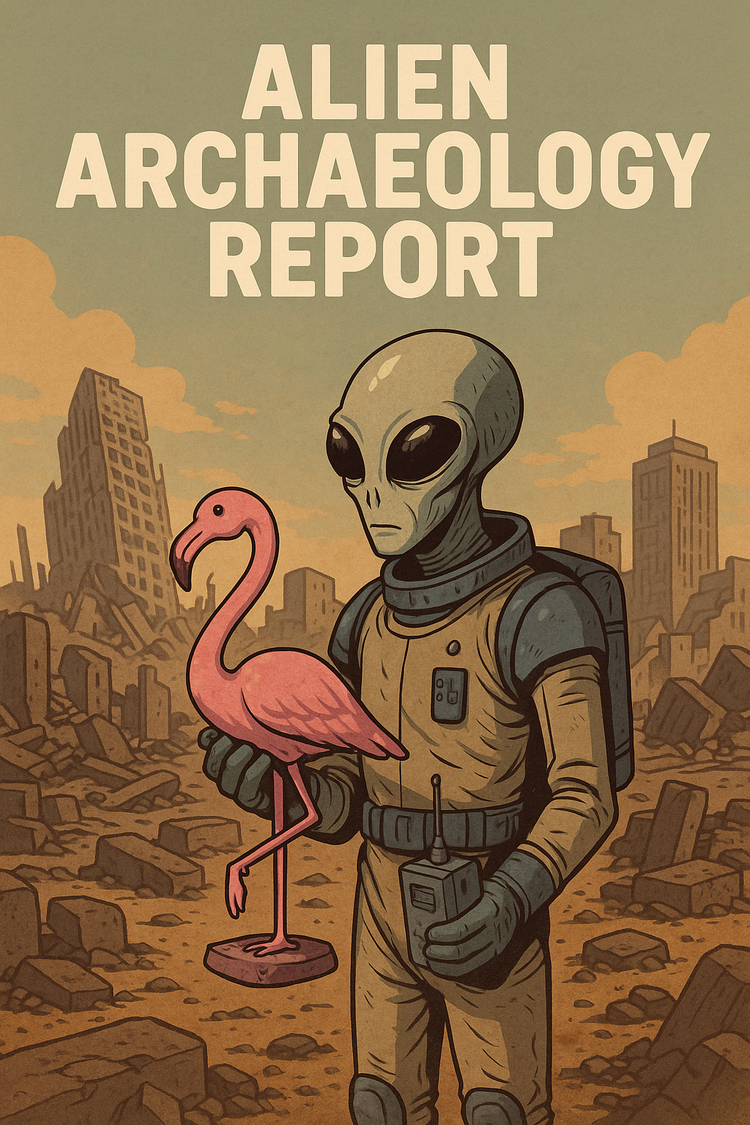

The real dream is expressive morphology. Tools that change shape to fit tasks. Swarms that coalesce into temporary bodies. Machines that feel friendly not because they mimic our limbs, but because they understand our fears. When emotional resonance is decoupled from mimicry, the door opens to forms we have not yet imagined. We do not need to ban humanoid bots. We need to stop pretending they are the end goal.

Let the hospital bots wear cardigans. Let the firefighting bots sprout insect limbs. Let the underwater welder look like an alien octopus. Let the billboard bot wear jeans if it helps sell insurance.

Just do not let the uncanny valley become the creative cul-de-sac. The future deserves more than a mirror with motors.

Member discussion